Why Ancient Egyptians Had Surprisingly Progressive Views on Mental Illness

An argument against magic

Many people assume the Ancient Egyptians understood the world around them through supernatural forces, and mental illness resulted from demonic possession.

Yet, I would argue this assumption doesn’t tell the whole story. I believe this ancient civilization had progressive views on mental illness based on the rational understanding of disease and treatment and a culture open to discussing mental health issues.

This perspective is important because there are vital lessons to learn from understanding beliefs and practices surrounding mental illness throughout the world.

Magic & Disease

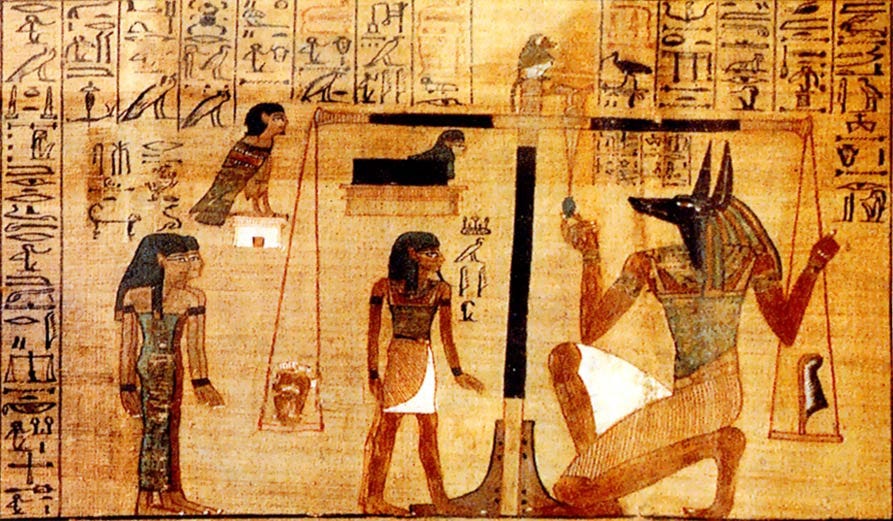

On the one hand, you have a civilization roughly 4000 years old reported to be overly reliant on magic. The beautiful tombs, incantations and amulets found in excavation sites support the view that everyone in ancient Egypt, from king to peasant, believed in an impersonal force controlling the universe, and powerful magicians could harness this power.

As a result, researchers believe magic was an essential component in Egyptian medicine. Diseases were supernatural in origin, and doctors and priest doctors would invoke spells and incantations as treatment. A medical text known as the Papyrus Ebers, dating back to 3000BC, includes over 700 spells to cure disease, including this one to cure a common cold :

Flow out, fetid nose, flow out, son of fetid nose! Flow out, you who break bones, destroy the skull and make ill the seven holes of the head!

On the other hand, Ancient Egypt is where the first dawn of modern medical care was found, including detailed knowledge of anatomy, performing surgical procedures using instruments, and understanding the cardiovascular system.

In addition, the discovery of the Edwin Smith Papyrus, an Ancient Egyptian medical text roughly 3000 years old, had the first recorded case studies in medicine. The text includes a title, instruction on the examination of the patient, diagnosis and prognosis, and recommended treatment.

Countering the common viewpoint that Ancient Egyptians used magic to cure illness, the evidence points to a rational method of medicine used in Ancient Egypt based on identifying the cause of disease and providing effective treatment, including mental illness.

Identifying causes for mental disorders

The Papyrus Ebers, composed in 1550BCE, describes mood disorders relating to dysfunctions of the heart and makes it one of the first examples in recorded history of an organic cause for mental illness.

When his heart is afflicted and has tasted sadness, behold, his heart is closed in, and darkness is in his body because of anger which is eating up his heart.

When the heart is miserable and is beside itself, behold it is the breath of the heb-xer priest that causes it through the hollow of his hand.

In other words, the Egyptians believed the heart was the centre of emotional and physical life, controlling all the actions of the body, including the arms, legs, vision and breathing.

Even emotions were expressed as various idioms referring to the heart. For example, being happy would be described as being long of heart and depressed as short of heart. In other words, the heart was expressed as the mind.

Although the medical community today believes mood disorders arise due to brain dysfunction in addition to psychological and social factors. What makes the ancient Egyptians remarkable is that they identified a reasonable, organic cause for mental illness over 3500 years ago, departing from the magical demonic possessions which dominated thinking in antiquity at the time.

They may not have been too far off either, with research into mood disorders showing an association with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Similarly, patients with heart disease have a higher risk of developing mood disorders.

This description of affective disorders in a 3500-year-old Egyptian text seems much more relatable then:

“When the heart is sad, behold it is the moroseness of the heart, or the vessels of the heart are closed up in so far as they are not recognizable under thy hand.”

Ancient Egyptian Psychoanalysis

Roughly 3 thousand years before Freud tried to tackle the issue, dream interpretations in the mentally ill were used as a diagnostic and therapeutic aid in Ancient Egypt.

A patient suffering from psychological distress would go to a sanatorium, a sleep temple dedicated to healing. They would be placed in a dark cell and prepare for the “therapeutic dream,” a hypnotic sleep state induced by lamps and burning perfumed wood. The priests would interpret the dreams arising from this sleep state by consulting the book of dreams, the oldest known manual of dream interpretation in the world, to find a cure in its pages.

The 3000-year-old papyrus is organized and divided into positive and negative images.

If a man sees himself dead, this is good; it means long life in front of him.

If a man sees himself eating crocodile flesh, this is good; it means acting as an official amongst his people.

If a man sees himself with his face in a mirror, this is bad; it means a new life.

While the ancient Egyptians believed the symbolic imagery in dreams could be interpreted through a dream dictionary, I would argue that the practice and development of dream interpretation for over half a millennia resulted in just as sophisticated an interpretation system as set up in modern-day psychoanalysis.

Although some may object to comparing the dream interpretation systems of ancient Egypt and Freudian psychoanalysis, one viewing dreams as prophetic visions from god and the other as unexpressed wishes, I would highlight that both emphasized the importance of dreams as a therapeutic aid for psychopathology.

I believe this strengthens my point that Egyptians attempted to move away from magical interpretations of mental illness and approached the discipline with a much more progressive and rational treatment method than assumed.

An open culture

Ancient Egyptian texts are filled with stories describing in intricate detail the depths of depression and despair faced by its inhabitants:

“He huddled up in his clothes and lay, not knowing where he was, his wife inserted her hand under his clothes and said ‘no fever in your chest, it is the sadness of the heart.”

‘ Now death is to me like health to the sick, like the smell of a lotus, like the wish of a man to see his house after years of captivity.’

The ancient Egyptians described the somatic manifestations of depression with surprising accuracy, and they discussed these symptoms openly. I believe the vast number of poems and tales describing a state of sadness and depression reflects a culture open to discussing these issues without the fear of stigmatization, allowing patients to seek help and treatment openly.

This poem below expresses rather beautifully a description of depression:

“describing depression, I feel my limbs heavy, I no longer know my own body, my eyes decline, my ears harden, my voice is speechless.

Should the Master Physician come to me? My heart is not revived by their medicine.”

And another:

Death is in my sight today,

like a man longs to see home,

when he has spent many years taken in captivity

The many poems similar to the above are eye-opening cultural commentaries of a civilization that openly discussed mental health issues and receiving treatments for psychiatric conditions, supporting my assertion that ancient Egypt had a very progressive outlook toward mental health.

This progressive outlook becomes even more apparent when comparing ancient Egypt to other ancient civilizations, such as Mesopotamia, which firmly believed that mental illness was due to demonic possession and patients would suffer stigmatization and exclusion.

Conclusion

Although this argument may seem important to only a small group of medical anthropologists and historians, it should concern anyone who cares about psychiatry and psychotherapy today.

Looking at the past offers a broad perspective from which we learn more about our present-day systems and how to evolve them.

If anything, it reminds us that mental illness hasn’t changed much in 4000 years. Only our understanding has ebbed and flowed throughout the millennia.

This is an excellent article! I don’t know if you know this, but many of your quotations of Egyptian texts are the same as some of the exercises in James Hoch’s Middle Egyptian Grammar. The poem about death was one of the trickier translation exercises for me.

Well researched and written.